698 – Three Words That Strike Fear in Vets and Owners

Three Words That Strike Fear in Vets and Owners

Host Laura Reeves is joined by Dr. Marty Greer talking about the three words that strike fear in both veterinarians and owners.

“These three things are what can take a normal, easy, lovely day at the veterinary clinic and turn it upside down and cause clients to have to wait and then swear at their veterinary team because they don’t understand why they have to wait because they had an appointment,” Greer said.

Those three words, according to Greer, are GDV (bloat), Pyo (pyometra) and HBC (hit by car).

Refresher on these three critical care situations:

Pyometra is a uterine infection.

“Fevers are almost never seen with pyometras,” Greer said. “And it’s a hard thing to understand how you can have a uterus full of pus and not run a fever. But apparently the uterus is a privileged organ and it allows for foreign things to happen in it. That could be a pyometra. That could be a puppy.

“So unfortunately, they almost never run a fever, so don’t rely on that to be a symptom. If you were waiting for a fever to happen, it means that the uterus probably just ruptured and the dog now has a belly full of puss instead of just a uterus full of puss. And when your belly is full of puss, you’re in big trouble. And so, if you’re waiting for a temperature, you’re decreasing your dog’s odds of survival.

“If your dog was recently in heat, they aren’t feeling well, they’re not eating well, they’re perhaps drinking buckets and buckets of water, maybe vomiting, maybe have a vaginal discharge, maybe not. Do not wait for a fever (to take the dog to the vet).”

GDV (gastric dilatation and volvulus) is bloat, where a dog’s stomach fills with air and may twist, causing a very rapid cascade of life-threatening events in the dog’s system.

HBC (hit by car) and other trauma is covered in our K9 911 First Aid seminar series linked here.

685 – Mastitis is not Metritis is not Pyometra

Mastitis is not Metritis is not Pyometra

Dr. Marty Greer joins host Laura Reeves to walk through the differentials in diagnosing possible infections in the breeding bitch, including mastitis, metritis and pyometra.

“There’s a lot of reasons that postpartum bitches can run a fever. So I think it’s a really good topic because when you go to the vet or if you know if you’re calling for a vet appointment or you’re getting to the vet, it can be a little more muddy than you think it should be.

“Before you call your vet with a sick postpartum bitch, take her temperature. Please take her temperature because the second thing the receptionist is going to ask you is what’s her temperature? And you’ll be like, I don’t know, I can’t find my thermometer. So have a thermometer dedicated to the dog, have a jar of Vaseline, and be sure that you’ve taken it and written it down. Because by the time your postpartum bitch is sick, you are stressed, you are tired, and you can barely remember your own name. So write down the stuff.

“How are the puppies doing? Are they gaining weight? Losing weight? Are they sick? Because there is a big difference. Both metritis and mastitis can cause the puppies to be sick as well. Because the bitch is sick. So mastitis is inflammation and infection of the mammary glands, and metritis is inflammation and infection of the uterus to be differentiated from pyometra.

“The top two differentials are always going to be metritis: infection of the uterus, inflammation of the uterus, and mastitis: infection, inflammation of the mammary glands. Now, just because the mammary glands are firm does not mean the bitch has mastitis. And just because the mammary glands are firm does not mean you automatically slam her on antibiotics.”

Marty continues with a complete discussion of metritis (within 24-48 hours of whelping), mastitis (not exclusively, but commonly 3-4 weeks post whelping) and pyometra which generally occurs when a bitch is not in whelp and normally is not accompanied by a fever.

Remember, if you enjoy our conversations, check out our new show! Recorded for you, your puppy buyers, your non-doggy friends and your cousin’s uncle’s girlfriend, the show is designed to reach the general pet owning public with reliable accurate information in an accessible format.

488 – Veterinary Voice: Congenital and/or Hereditary Definitions

Veterinary Voice: Congenital and/or Hereditary Definitions

Dr. Marty Greer, DVM joins host Laura Reeves for a deep dive on the question of congenital vs hereditary disease definitions.

“So congenital is something you’re born with, not necessarily inherited, but something you’re born with. Genetic is something that you carry the DNA for,” Greer said. “If you’re born with something, it’s congenital. So, if you’re born with the umbilical cord wrapped around the puppies leg and the leg doesn’t fully develop, that’s congenital because they were born with it but it wasn’t genetic, it was an accident that the cord wrapped around the way. Just ’cause you see it at birth doesn’t mean it’s genetic.

Many diseases, Greer noted, “there is a genetic basis” with a “trigger.”

“An epigenetic or an environmental trigger, is there a nutritional component to it, was there some exposure to a chemical that predisposed the patient to it. So that’s where it starts to get muddy. Not everything that’s genetic is easy to figure out the inheritance pattern for. The things that we can DNA test for now are pretty much autosomal recessive genes,” Greer said.

“Are we throwing dogs out of our gene pool because they have something that’s genetic and we don’t have the right test for it, then we may never have a test for it or it’s not genetic or have some genetic and epigenetic and environmental component to it? As much as we think we understand this stuff, it’s not easy,” Greer added.

“The more we know, the less we know. As we start adding this information to our knowledge base, it’s going to become evident to us that what we thought isn’t really true… all information is valuable, but if you don’t apply it correctly, you’re going to end up bottlenecking your gene pool, as you’re going to throw good dogs out.”

471 – Myth Busting in Veterinary Medicine

Myth Busting in Veterinary Medicine

Dr. Marty Greer, our veterinary voice, joins host Laura Reeves for a fun episode by multiple listener request. They tackle old wives tales and do a bit of myth busting on veterinary medicine.

Q: Do bitches in season cycle together?

Yes.

“I think it’s true. I really do believe that happens. There’s hormones, there’s pheromones. It’s called convent syndrome or dormitory syndrome in humans. Absolutely it happens in dogs too.

“There’s a reason for that… it was thought that bitches would cycle together so that there would be additional mothers available to lactate should puppies be orphaned or otherwise the bitch wasn’t available to nurse her puppies.

“They cycle together, they all come into heat at the same time, they start excreting or secreting a pheromone weeks before they come into heat so that they can start recruiting male dogs so that they are available at the time that the bitch is ready to breed.

Q: Do intact male dogs need drugs when bitches are in season?

Yes.

“There’s no reason not to put a male dog on some kind of an anti anxiety medication.”

Q: Matings can happen through chain link?

Yes

“The drive to have a sexual encounter is a very, very strong drive in every species. We all know that … we’ve got pictures of dogs that know how to unlatch their kennel door, walk across the top of a kennel, drop down into the female’s pen, breed the female and then walk back out and get back into their own kennel. We have proof that these dogs are doing this because we now have video in people’s kennels.

“It’s a fascinating study in canine behavior but yes the boys do have a pretty strong drive and the females are very cooperative at that point. Yes you can use drugs. Keeping them separated physically is useful. But there is nothing that you can do that they can’t undo faster because they’re spending 23 hours and 49 minutes a day trying to figure out a way to get that particular encounter to happen and you spent 11 minutes that day figuring out a way for it not to happen.

“Anybody that tells you that they’ve never had an accidental breeding, that owns both males and females that are intact at their house, is either lying to you or it hasn’t happened to them yet.

Q: Does chlorophyll when given immediately when the bitch comes in season reduce the odor?

No

“It’s gonna help to a small extent, but it’s not going to be enough to cover up everything. No charcoal, chlorophyll, vanilla, Vicks, you name it, all the things that people try (is) going to overcome every single molecule. Remember dogs have probably 10,000 times the number of scent cells an inside their nose (than people).

Q: Will females that have pyometra always have a fever?

No.

“The uterus is a privileged organ. It isolates proteins that aren’t part of that particular individual’s DNA. That allows the little puppies to develop and grow and be born as little puppies and the uterus doesn’t say ‘oh you don’t belong here and have some kind of immune response that kicks them out.'”

224 — Veterinary Voice: Pyometra is an Emergency

Pyometra is a life threatening disease

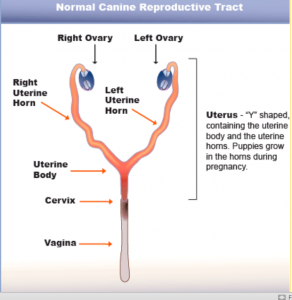

Pyometra is a severe bacterial infection with accumulation of pus within the uterus. Though it often occurs with middle-aged or older unspayed females, younger dogs are sometimes affected. Pyometra most commonly develops a few weeks after a heat cycle. The condition results from hormonal changes that decrease the normal resistance to infection. As a result, bacteria enter the fluid in the uterus and large volumes of pus can accumulate.

Pyometra is a severe bacterial infection with accumulation of pus within the uterus. Though it often occurs with middle-aged or older unspayed females, younger dogs are sometimes affected. Pyometra most commonly develops a few weeks after a heat cycle. The condition results from hormonal changes that decrease the normal resistance to infection. As a result, bacteria enter the fluid in the uterus and large volumes of pus can accumulate.

Signs of Pyometra include loss of appetite, excessive thirst and urination, lethargy, and/or vomiting. Sometimes, there is a vaginal discharge. The disease may develop very slowly over several weeks.

This condition often requires emergency surgery, provided the animal is stable. Surgery consists of removing both ovaries and uterus, which not only corrects the condition, but also eliminates bothersome heat cycles. Because the patient is ill and the uterus is infected, the surgery is more complicated and carries a higher risk than a routine spay. Ultrasound and blood tests are useful in both diagnosing and evaluating surgical risk. Post-operative treatment includes antibiotics and intravenous fluids.

For dogs who are in a breeding program, Dr. Marty Greer, DVM provides information in the podcast about medical management that may avoid the spay surgery.

Pyometra

From Dr. Greer…. “Your pet has presented with a condition called pyometra, or a uterine infection. These can be life-threatening, and most cases will not resolve without surgery. Pyometra usually occurs 1-5 weeks after the last heat cycle. In this illness, the uterus has filled up with pus (white blood cells and bacteria) and is at risk for rupturing if not treated immediately.

Prior to surgery, we will stabilize your pet with intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and pain medications. Most patients with pyometra are very sick – with either a very high or very low white blood cell count, fever, dehydration, a low blood sugar, and vomiting and diarrhea. As soon as your pet is able to tolerate anesthesia, we will start surgery to remove the uterus.

Your pet will be in the hospital for at least 2-5 days, depending on how she does during surgery and afterwards. It is important to know the possible complications of pyometra surgery. These include:

- Peritonitis is the most common. This means infection within the abdomen. It is treated with antibiotics, IV fluids, and may require additional surgery and drainage.

- Rupture of uterus in surgery. The uterus is often very thin and easily damaged. It is possible that it can rupture during surgery, spilling pus into the abdomen. This can prolong the hospitalization for several days.

- Aspiration pneumonia. Fluid and food sometimes bubble up into the throat and mouth during surgery. This can be inhaled into the lungs, leading to pneumonia. Every precaution is taken to avoid this, but it still happens in some cases.

- Sepsis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and disseminated intravascular coagulation can also occur before, during, or after surgery. These are uncommon complications in which the white blood cell count drops, the patient develops or continues to have a fever, sometimes develops difficulty breathing and difficulty with normal blood clotting. These are not common but can occur. If they do, very aggressive treatment must be undertaken to save your pet and can significantly prolong hospitalization and lead to death.

- Acute kidney failure can occur before, during, or after surgery. This is not a common complication but can happen. Often patients will also have a urinary tract infection. Once your pet is stable, eating, comfortable and able to take oral medications, discharge home can be discussed with the doctor. ”