382 – Skye Terriers: Hardy, Devoted Breed of the Scottish Isles

Skye Terriers: Hardy, Devoted Breed of the Scottish Isles

Skye Terrier puppy

Our panel of Skye Terrier breeders represents nearly 150 years combined experience in the breed. Michael Pesare, Elaine Hersey and Karen Turnbull join host Laura Reeves to share their love of this hardy, devoted breed of the Scottish Isles.

Depicted in art through centuries and with history dating back to the 1500s, the Skye is an old breed.

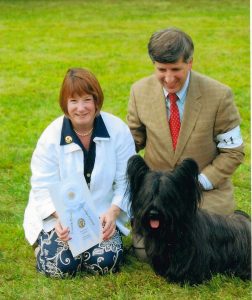

Michael Pesare

“The Skye definitely shares his heritage with a number of other terrier breeds from the Western Isles,” Pesare said, “the West coast of Scotland, where it can be quite rugged, damp, cold, rocky … breeds like the Cairn, the Scottie, the Westie… they were kept by the land owners to rid the farms of vermin. But not just small vermin, we’re talking Otter, Badger, foxes all the vermin that would do damage to the crops… there are references to long legged terriers and short crooked legged terriers going back to the 1500s, and so our Skyes definitely have a very long history.”

An achondroplastic breed, the long, low Skye is heavy bodied and heavy boned.

Karen Turnbull

“This is actually a very, very healthy breed,” Turnbull said. “I think because they’ve been rare that’s worked in their favor and there are very hardy breed, a sturdy breed … one question that we get frequently because they are a long and low breed I think people instantly think back problems. Our breed is not prone to back problems. The first thing I do when people say that is I invite him to feel the back and feel the legs. They’re always surprised because they have so much bone and there’s such a sturdy dog … people are always surprised at how much dog is underneath that coat.”

Made famous for their loyalty by the story of Grayfriars Bobby, the Skye is deeply devoted to its family.

Elaine Hersey

“It’s a breed that wants to be with its person,” Hersey said. “They are very, very sensitive. They are very intuitive. They love their people. They’re not a breed that you can put out in the backyard and forget about. They need to have, I think, early socialization. They need to have continued socialization as a puppy if you want to have the best Sky you can. So they need somebody that’s committed to doing the work and then they’re going to have a wonderful, wonderful dog.”

For more information about the Skye Terrier, visit the Skye Terrier Club of America.

211 – Dwarfism: When the Right Gene Goes Wrong

The Dark Side of the Dwarf Gene

Dr. Theresa Nesbitt talked last week about the purpose-bred dogs that evolved with short legs to do very specific jobs. Today she talks about “the dark side of the dwarf gene” and what happens when things go wrong when you’re trying to do it right.

Dwarf genes have been around for more than 4000 years, Nesbitt said. They are solidly entrenched in some breeds that are specifically “fit for function” for the job they were meant to do.

“Everything that isn’t normal, isn’t pathological,” Nesbitt said.

Too much of a good thing

Sometimes, though, breeders can get “too much of a good thing,” Nesbitt added. She also shared tremendous information on the various genetic disorders of dogs who aren’t supposed to be dwarfs.

Nesbitt provided layman’s translation for a lot of medical terminology. She helped decipher topics like retro genes, epigenetics, genes that inadvertently land on the wrong chromosome and more.

Making words like achondroplasia make sense to those of us without a medical degree is a gift that Nesbitt shared throughout this episode. “Chondro,” for example, refers to cartilage, Nesbitt said, and “plasia” means growth. The dwarfism gene affects the rate at which animals (including humans) produce cartilage.

“The growth plate at the end of the long bones is like a disc of cartilage that keeps making longer bone,” Nesbitt said. “It pushes out like a pasta machine extruding bone in a perfect column.”

Genes are a “recipe book”

Nesbitt’s discussion of “layering genes,” autosomal recessive genes and the progress being made in the research community as they acquire more advanced understanding of how all of these systems work is fascinating. She also brought to the discussion ways in which research on canine genetics is benefitting people.

Intervertebral disc disease, in which calcification develops between the discs, is an area Nesbitt said research is making tremendous strides in identifying the specific genes responsible.

Genes provide a “recipe book” to the cells, for which epigenetics are the “family notes,” Nesbitt said. She added that the environment can change or modify genetics.

This is a “must listen” episode. And probably more than once! Nesbitt’s enthusiasm for the topic and ability to translate into layman’s terms is invaluable.

207 — Short-Legged Dogs Bred for a Purpose

Short-legged dogs and Wrap-around fronts

Theresa Nesbitt is a retired ob-gyn physician with a focus on skeletal abnormalities. Her hobby is breeding and exhibiting Glen of Imaal Terriers and Dachshunds. The combination of these two passions led her to extensive study of the conformation of purpose bred, short-legged dogs and wrap-around fronts.

Theresa Nesbitt is a retired ob-gyn physician with a focus on skeletal abnormalities. Her hobby is breeding and exhibiting Glen of Imaal Terriers and Dachshunds. The combination of these two passions led her to extensive study of the conformation of purpose bred, short-legged dogs and wrap-around fronts.

“It’s an interesting puzzle,” Nesbitt said. “There is a lot of overlap between the breeds that have this conformation.”

Genetics and expression of dwarfism

Researchers have just recently identified the genes responsible for this function, Nesbitt said.

“It’s a very, very old gene,” Nesbitt observed. “And a very interesting kind of gene. Literally it made a second copy, snuck back into the nucleus and puts itself on the recipe book. Two copies of the gene and the second one doesn’t have instructions. We call it a retro gene.”

Understanding how and why genes turn on and off is going to help the medical field understand cancers and more in the future, Nesbitt noted

What’s your job description

Through history, people in widely varied areas of the world found purposes for short-legged dogs.

“They found the gene in the gray wolf. It wasn’t expressed, but it was there to be inherited,” Nesbitt said. “It popped up in many places and became a purpose-bred gene because, depending on the task you wanted to do, a short-legged dog can do a lot of different jobs.”

Vermin hunting and going to ground were amongst the most common purposes for which people developed and perfected the genetic inheritance for short-legged dogs.

Badger hunting was the most dangerous job and required the most experienced dogs. A badger “sett” is like a series of tubes and chambers, Nesbitt said.

Other short-legged breeds include corgis, who were low enough to duck under the kicking heels of cattle, Basset Hounds, Glen of Imaal Terriers who were used, amongst other jobs, to run on a “turnspit.”

Glen of Imaal Terriers were bred with short legs so they could run on a turnspit and fit under the spoke of the wheel.

“A turnspit is like a hamster wheel,” Nesbitt said. “It’s a labor-saving device to turn meat over the fire etc. The dogs have to fit under the middle spoke. They have to have short legs.”

It’s what’s up front that counts

In most of the short-legged breeds, the front construction is designed in such a way that the front “wraps” around the rib cage, particularly those breeds in which the chest is below the level of the elbows.

The deep chests, pronounced prosternum and extensive keel (sternum) on these breeds again serves a purpose. Dogs that dig underground rest on their keel as they dig with their front legs, throwing dirt to the side much like a badger does. Taller terriers throw dirt between their back legs as most of us are used to seeing.

The overall front assembly and shoulder construction of short-legged dogs, whether the legs are underneath dog or placed out on the side, also is affected by the job they were designed to do.

When the front wraps around the ribcage, in some cases it leaves the dogs with slightly out-turned feet, to a greater or lesser degree based on the job and overall substance of the dog.

“A fiddle front is always undesirable,” Nesbitt said. “When the forelegs come very far in and point very far out. There is no sense that any job would require that construction.”

Join us next week as Theresa and I talk about when achondroplasia goes wrong.

And stick around for Allison Foley’s Tip of the Week from the Leading Edge Dog Show Academy and what to do about dogs blowing coat.